Research

This page shows my research areas and the current results of the research achieved so far.

Organisation

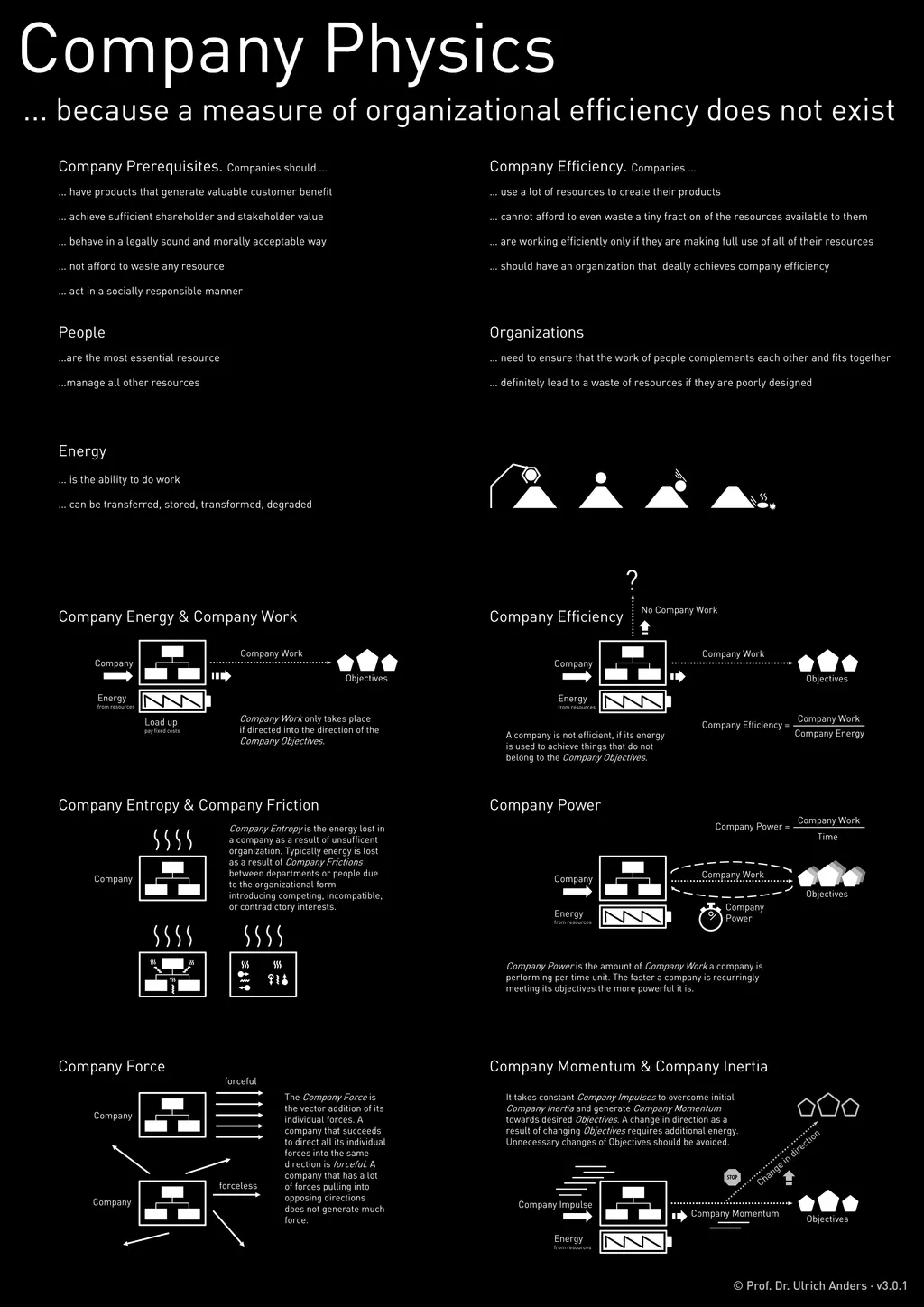

Management contains two significant and central tasks: organisation and decision taking. In this context, my research deals with the questions of the compatibility of interests and organisational efficiency. In the scientific world there does not seem to exist a commonly agreed measure for organisational efficiency. In order to describe organisational efficiency I devised the concept of Company Physics.

The question of organisational efficiency is extremely important, because an inefficient organisation always and inevitably leads to a waste of the company’s resources. A company facing the increasingly competitive pressure and the demand for sustainability can simply not accept such a situation. To describe the causes of organisational inefficiency I put together the 10 Organisational Mudas in analogy to the Mudas known from the area of operations.

Furthermore, in my research I pose the question what could be an appropriate organisational form for the entrepreneurial challenges in the 21st century with its (digital) business models. As one potential organisational form I have conceptualized the organisational model of a Harmonic Organisation©, which can be considered as a form of an agile organisation.

Agile organisations are typically not based on hierarchies. Therefore, they need to find an alternative structure. The central structure in a Harmonic Organisation© is the stringent customer-supplier-relationship across the whole of the company which also ensures the systemic alignment of all interests. The second core ideas is to derive responsibilities not longer from organisational (silo) functions but from Ownership. Because ownership is unique, responsibility will be too. This solves the problem of overlapping vertical and horizontal responsibilities on the one hand and non-existent or rejected responsibilities on the other hand. Companies can have only four entities that can be owned: resources, tasks, products, and assets so the allocation is in principle rather easy.

Business Models and Business Planning

I work systematically on (traditional, new, digital, and innovative) business models. As a result I have come up with the Business Model Components Map (BMCM).

This map is an advancement to existing business model concepts. The BMCM adds the important elements of a business model that have not been addressed up until now: company value, liquidity, owners & capital, society, and environment.

The Business Model Components Map is based on a fundamental recognition of what the mechanism of Companies is: Other then typically stated in the research literature, companies not only transform resources into valuable products and generate profits from selling them. The recognition is that companies not only do this but from doing this they also build (tangible and intangible) assets that then become resources again. This built-up assets base is often the differentiating factor between successful and less successful companies.

Concept Thinking

One of the central elements in any business model is the product. Therefore, I devised a process for the systematic conceptualizing of products. This process should also generate and facilitate possibilities for (digital) marketing. I have termed this process Concept Thinking — and it can potentially supplement Design Thinking.

Project Management Maturity, Project Control and Path Dependence

In the area of Project Management exist a vast number of textbooks, training and educational courses, seminars, or certifications. Nevertheless, project failures, reduced scopes, time and budget overruns can still be frequently observed. Even prominent projects that get a lot of public scrutiny often seem to fail.

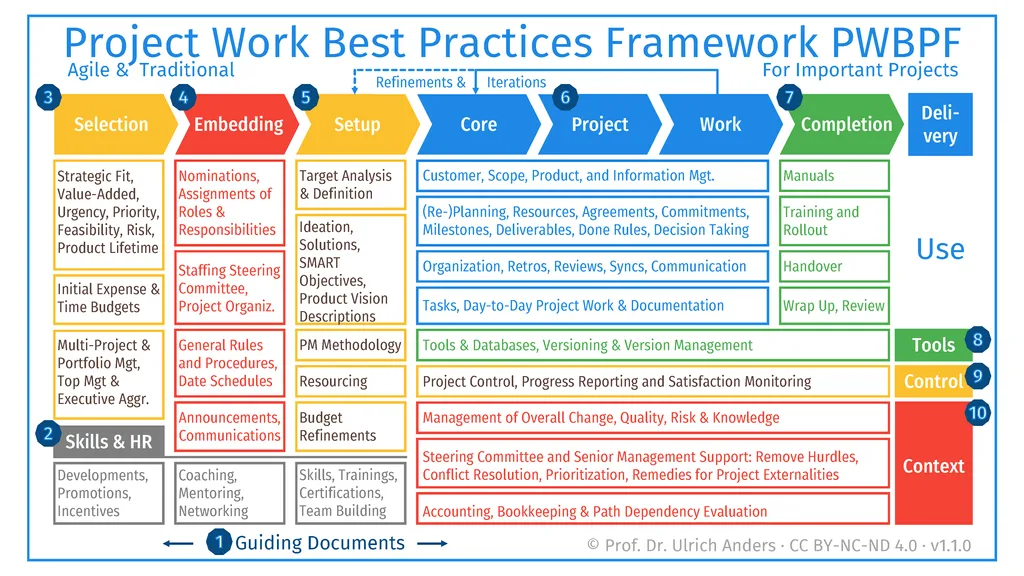

One reason why projects fail is that companies who carry out project are simply not mature enough. They do not have standardized mechanisms for project selection, embedding and organisational setup. They also do not provide their project managers with the necessary guiding documents, HR measures, infrastructure, tools, templates or organisational setup. As a result project managers struggle along and often do not succeed to control the chaos naturally resulting from projects.

To provide a guideline I have developed the Project Work Best Practices Framework PWBPF and a Project Management Maturity Score to evaluate the maturity of the company with respect to project management.

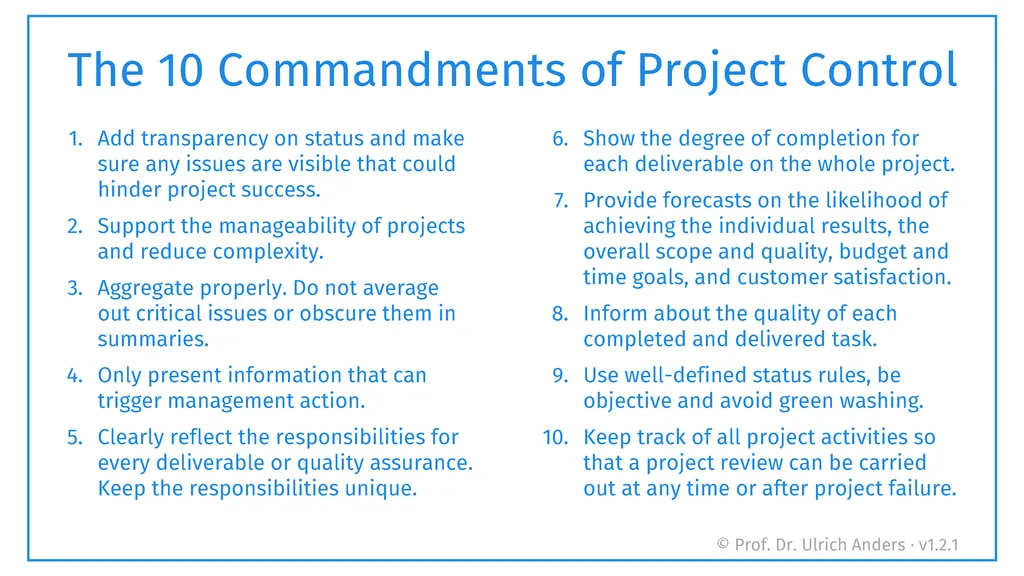

Another reason why projects fail may certainly be the ever increasing complexity of projects. In contrast, I have the hypothesis that the used project control instruments often are simply not good enough. In fact, I assume that project control may too a large degree be a forgotten or ill-defined discipline. Text books do not even seem to cover the area of project control or only in a very subordinate way.

A lot of people get educated to be project managers, but only a few become project controllers even though the skill set may be as demanding. As a result a project may lack the rigorous project control, the necessary issue transparency and an overview of the performed quality assurance. As a result of this realization, I have developed the 10 Commandments of Project Control.

In addition, I have made the following observation: a reason why projects are continued even though the project is in trouble seems to be Path Dependence. Path dependence is a well recognized phenomena in the area of social sciences, but has not been properly applied to project management yet.

On Strategy

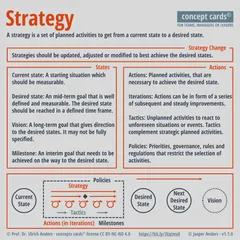

There is a large misconception what strategy is. Accordingly, the term strategy is often used in the wrong manner. It is widely accepted that strategy is a set of planned activities to get from a current state to a desired state.

The misconception is coming from how the term strategy is often used. It is typically assumed, that the strategy is developed on the so-called “strategic layer”, e.g. on or with the C-level of a company.

Contrary to the name, however, the task of the “strategic layer” of a company is not to develop the strategy but rather the desired state. The desired state is a concrete form of a target situation that can well be a step into the direction of a vision. Developing a desired state is quite hard as it needs to be potentially achievable and realistic in a given time frame.

A desired state is by the way not formulated in terms of P&L or balance sheet numbers. It describes a situation with which the “strategic layer” assumes that certain P&L or balance sheet numbers can be achieved.

Only if the desired state is well formulated, the strategy can be derived. This is typically done by the more operational layers in the company. All activities that are necessary to achieve the desired state then form the strategy.

The task then of the “strategic layer” is to enable the operational layers to implement the strategy by resourcing and prioritizing everything accordingly and by finding the best organization to combine the various efforts.

The implementation of any strategy must then be tracked and, if needs be, updated, adjusted or modified. The same holds true if the desired state changes.

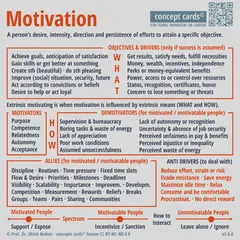

Models of Motivation

There are a number of motivational models. However, many of them suffer from two aspects: (1) the terminology is not well defined, (2) they only address partial aspects of motivation, i.e. what drives or hinders motivation. My research is trying to fill those gaps.

Terminology: There is no such thing as intrinsic motivation or extrinsic motivation. Motivation always comes from within. The difference is not in the motivation but in the objectives: Intrinsic objectives are set by the persons themselves. Extrinsic objectives are offered by outside parties.

Partial models: Even if a person is in general highly motivated to achieve intrinsically or extrinsically set objectives and given that there are no fundamental demotivators in the context, this person might still face so-called anti drivers. Anti drivers are opposing the drivers, i.e. the objectives. All people are facing those anti drivers and their intensity may depend on daily form. To overcome anti drivers there are a number of allies that can be employed.

Generally speaking, neither anti drivers nor allies are typically part of motivational models. As a result, many empirical surveys are also flawed as the underlying models are partially incomplete. For instance, such surveys do not distinguish between generally being motivated, but facing anti drivers and being unmotivated.

Knowledge Transfer and Teaching Methods

Finally, I have started to scientifically look into the subject of teaching methods. Teaching in university and business schools is going to change over time. It will turn from knowledge-based teaching to competence or skill based teaching. A competence or skill is only achieved if one knows how to apply the acquired knowledge and if the application was sufficiently practiced.

Modern teaching methods may not only help to make the learning experience of students better, they are also more rewarding if the lead to a noticeable skill. Moreover, they may also help to solve some societal challenges in the context of schooling and language acquisition.

The underlying assumption of my research is that the transfer of knowledge can be split into two parts: (1) the knowledge preparation and (2) the knowledge application.

The more the knowledge itself is available in form of digital content, the more lies the future of teaching in ensuring the knowledge application. The lecturer or teacher will most likely not prepare the presentation of the knowledge any longer but will become a coach and tutor who helps with the application of the knowledge in order to help the student to produce a skill. For this the lecturer or teacher will provide group and individual support.

Software will play a significant role in this context as it enforces the application of knowledge. Therefore, on top of learning concepts of interactive learning, blended learning or competence-based learning I am using software-based learning (e.g. with Business Planner Online, Camunda, DaVinci Resolve, Excel, GitHub, ImageMagick, JavaScript, Markdown, MURAL or Miro, OBS, MS Project, Pandoc, ProjectLibre, Pitch, R, THE PROJECT STATUS, Trello, VS Code, etc.)

Concepts

- Anders, Ulrich (2025): »Business Model Components Map«, v9.1.0.en

- Anders, Ulrich (2025): »Business Model Components Map«, v9.1.0.de

- Anders, Ulrich (2025): »concept card© — Company«, v1.5.0

- Anders, Ulrich (2025): »concept card© — Motivation«, v3.4.0

- Anders, Ulrich / Anders, Jasper (2024): »concept card© — Strategy«, v1.1.0

- Anders, Ulrich (2024): »concept card© — Business Model«, v1.6.0

- Anders, Ulrich (2023): »concept card© — Project Status«, v1.0.0

- Anders, Ulrich (2023): »concept card© — Project Maturity«, v1.0.0

- Anders, Ulrich (2022): »Project Work Best Practices Framework«, v1.0.0

- Anders, Ulrich (2022): »concept card© — Scrum, v1.2.0

- Anders, Ulrich (2022): »concept card© — Objectives-Resources-Matrix, v1.0.0

- Anders, Ulrich (2022): »concept card© — Project Path Dependence«, v1.0.0

- Anders, Ulrich (2022): »concept card© — Organisational Efficiency«, v1.5.1

- Anders, Ulrich (2022): »concept card© — Organisational Design Language«, v2.5.0

- Anders, Ulrich (2022): »concept card© — Organisation«, v2.2.0

- Anders, Ulrich (2022): »concept card© — Ownership«, v1.4.0

- Anders, Ulrich (2022): »concept card© — Power«, v1.1.0

- Anders, Ulrich (2022): »concept card© — Company Principal Components«, v1.2.0

- Anders, Ulrich (2022): »concept card© — Leadership«, v2.2.1

- Anders, Ulrich (2022): »concept card© — Feedback«, v1.0.0

- Anders, Ulrich (2022): »concept card© — Innovation«, v1.0.0

- Anders, Ulrich (2022): »concept card© — Operations-Innovations-Matrix«, v1.0.0

- Anders, Ulrich (2021): »concept card© — Company Culture«, v1.0.0

- Anders, Ulrich (2021): »concept card© — Company Culture Spectrum«, v1.0.0

- Anders, Ulrich (2021): »concept card© — Semantic Versioning, v1.1.0

- Anders, Ulrich (2022): »concept card© — Agile«, v1.0.0

- Anders, Ulrich / Monti, Alessandro (2020): »concept card© — Pricing«, v1.5.0

- Anders, Ulrich (2020): »concept card© — Complexity Reduction«,v1.0.0

- Anders, Ulrich (2020): »concept card© — Project Control«, v1.3.0

- Anders, Ulrich (2020): »concept card© — Project Management«, v1.1.0

- Anders, Ulrich (2019): »SQUID — don’t SWOT: a Better Analysis Framework«, v1.1.0

Working & Discussion Papers

- Anders, Ulrich (2018): »Introduction into the Harmonic Organisation©: A new organisational model for sustainable companies and management in the 21st century«, Proceedings of The 8th International Conference on Sustainability and Responsibility, Cologne, 28-11-01.

- Anders, Ulrich (2018): »Company Physics: A language for describing organisational efficiency«, Proceedings of The 8th International Conference on Sustainability and Responsibility, Cologne, 28-11-01.

- Anders, Ulrich (2018): »Company Physics: A Poster«, The 8th International Conference on Sustainability and Responsibility, Cologne, 2018-11-01.

- Anders, Ulrich (2019): »Projektmanagement: Grundlagen, Ansätze und die Vermeidung typischer Fehler«, aktualisiert 2019-02-09.

- Anders, Ulrich (2017): »JavaScript in der Software-Architektur: Eine Darstellung für Manager & Entscheider«, 2017-10-22.

- Anders, Ulrich (2017): »Erprobte Ansätze aus dem Softwareumfeld übernehmen: Was Unternehmen und die BWL nutzen können«, 2017-08-31.

- Anders, Ulrich (2017): »Concept Thinking: Ein innovativer Ansatz im Produktdesign und Marketing«, 2017-05-18.

- Anders, Ulrich (2017): »React Redux Concept Workflow«, aktualisiert 2017-09-09.

- Anders, Ulrich (2017): »IT-Landschaften kartografieren«, 2017-02-02.

- Anders, Ulrich (2016): »Industrie 4.0: Kern, Architektur und Herausforderungen«, 2016-10-26.

- Anders, Ulrich (2016): »Organisation ist eine Ressource«, 2016-08-31.

- Anders, Ulrich (2016): »Die Hauptkomponenten von Unternehmen«, 2016-04-05.

- Anders, Ulrich (2016): »Die ideale Organisation«, 2016-03-19.

- Anders, Ulrich (2015): »Komplexität im Unternehmensumfeld«, 2015-09-08.

Publications

- Anders, U. (2004): »An Integrated Framework for the Governance of Companies«, Operational Risk, März 2004, 24–28.

- Anders, U. / Trimborn-Ley, S. (2004): »Woran Projekte scheitern«, Zeitschrift für das gesamte Kreditwesen, Ausgabe Technik 1/2004, 19–23.

- Anders, U. / van den Brink, G-J. (2004): »Implementing a Basel II Scenario-based AMA for Operational Risk«. In Ong M.K. (Ed.): The Basel Handbook«, Risk Books, 343–368.

- Anders, U. / van den Brink G-J. (2003): »Betrachtung operativer Risiken in Transaktionsbanken. 2 In Lamberti H. J., Marliere A, Pöhler A. (Hrsg.): Management von Transaktionsbanken«, Springer, 241–262.

- Anders, U. / Platz, J. (2003): »Creating an OpRisk Loss Collection Framework«, Operational Risk, September 2003, 24–27.

- Anders, U. / Sandstedt, M. (2003): »Self-Assessments zur Bewertung operativer Risiken«, Deutsches Risk, Juli 2003, 27–31.

- Anders, U. (2003): »Implementing a Scenario-based AMA, Operational Risk«, June 2003, 24–27.

- Anders, U. / Sandstedt, M. (2003): »Self-Assessments for Scorecards«, Risk, February 2003, 39–42.

- Anders, U. / Sandstedt, M. (2003): »An Operational Risk Scorecard Approach«, Risk, January 2003, 48–51.

- Anders, U. (2003): »The Path to Operational Risk Economic Capital. In Carol Alexander (Ed.): »Mastering Operational Risk«, Prentice Hall, 215–226.

- Anders, U. (2001): »Qualitative Anforderungen an das Management operativer Risiken«, Die Bank, 6/2001, 442–446.

- Anders, U. / Overbeck, L. (2000): »Spezifisches Risiko für Unternehmensanleihen«, Handbuch für das Risikomanagement, Uhlenbruch, 245–268.

- Anders, U. (2000): »RaRoC — ein Begriff, viel Verwirrung«, Die Bank, 5/2000, 314–317.

- Anders, U. / Korn, O. (1999): »Model Selection in Neural Networks«, Neural Networks, 12, 309–323.

- Anders, U. / Korn O. / Schmitt, C. (1998): »Improving the Pricing of Options — A Neural Network Approach«, Journal of Forecasting, 17, 369–388.

- Anders, U. / Szczesny A. (1998): »Prognose von Insolvenzwahrscheinlichkeiten mit Hilfe logistischer neuronaler Netzwerke«, Zeitschrift für Betriebswirtschaftslehre und Forschung, 10, 892–915.

- König H. / Körting T. / Anders, U. (1998): »Zur Bildung von Wechselkurserwartungen — Eine Untersuchung auf der Grundlage des ZEW–Finanzmarkttests«. In Galler, H. P. / Wagner, G.: »Empirische Forschung und wirtschaftspolitische Beratung«, Campus, 150–166.

- Anders, U. (1997): »Statistische neuronale Netze«. Vahlen Verlag.

- Anders, U. / Hann, T.-H. / Nakhaeizadeh, G. (1997): »Testing for Nonlinearity with Neural Networks — A Study for Daily $/DEM Exchange Rates«. In Weigend, A. S. / Abu-Mostafa, Y. S. / Refenes, A.-P. N (Eds.): »Decision Technologies for Financial Engineering«, Proceedings of the Fourth International Conference on Neural Networks in the Capital Markets (NNCM-96).

- Anders, U. (1997): »Die statistische Verteilung der Gewichte von neuronalen Netzen in finiten Datenmengen«. In Nakhaeizadeh, G. (Hrsg.): »Data Mining — Theoretische Aspekte und Anwendungen«. Physica, 279–288.

- Anders, U. (1997): »Neural Network Pruning and Statistical Hypotheses Tests«, Proceedings of the ICONIP ’97.

- Anders, U. / Korn O. (1997): »Modelling Neural Networks with Sequential Hypotheses Tests«, Proceedings of the ICONIP ’97.

- Anders, U. / Korn O. (1997): »Sequential Hypotheses Tests for Neural Networks«, Proceedings of the ESANN ’97 conference.

- Anders, U. (1996): »Statistische Grundlagen neuronaler Netzwerke«. In: Schröder, M. (ed.): »Quantitative Verfahren im Finanzbereich: Methoden und Anwendungen«. ZEW Wirtschaftsanalysen Bd. 5, Nomos Verlag.

- Anders, U. (1996): »Was neuronale Netze wirklich leisten«. Die Bank, 03/1996, 162–165.

- Anders, U. (1996): »Statistical Model Building for Neural Networks«. In Albrecht P. (Hrsg.): »Aktuarielle Ansätze für Finanz-Risiken«. Verlag Versicherungswirtschaft Karlsruhe, 963–980.

- Anders, U. (1995): »Neuronale Netzwerke in der Ökonometrie«. ZEW Discussion Paper 95–26.